News

Northern Nigeria’s Future Demands the Pyramid Blueprint for Development

By Sam Agogo

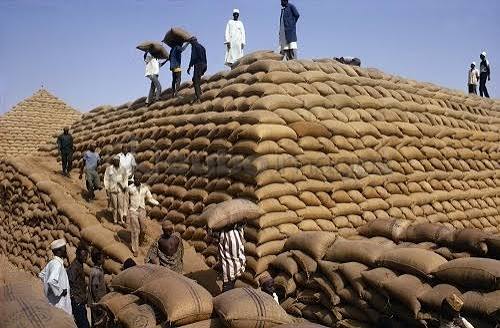

Northern Nigeria’s history is written in pyramids—vast towers of groundnut sacks that rose across Kano in the 1940s and 1950s, shimmering under the sun as monuments to discipline, enterprise, and collective resolve. These pyramids were more than agricultural storage; they were symbols of a thriving economy that placed the North at the center of global trade. They embodied a system where smallholder farmers, visionary traders, and organized marketing boards worked in harmony to transform harvests into wealth, funding schools, hospitals, railways, and industries that carried the region into modernity. In their grandeur, the pyramids told the story of a people who could turn the soil beneath their feet into prosperity that reached far beyond Nigeria’s borders.

The inside story of the pyramids begins with the colonial economy of the 1940s. Britain, seeking to integrate Nigeria into global trade, encouraged the mass cultivation of groundnut and cotton in the North. Farmers, often working small plots, produced in staggering quantities. The Northern Nigeria Marketing Board purchased these crops, stacked them into pyramids in Kano, and shipped them through rail lines to Lagos ports for export. The pyramids were not just storage—they were a spectacle, a visible assurance that the North was producing enough to feed industries abroad while financing development at home.

By the early 1950s, Kano had become the beating heart of Nigeria’s export economy. The pyramids financed the expansion of the Kano–Lagos railway line, ensuring that produce could move efficiently from the hinterland to the coast. This rail infrastructure became the backbone of trade, connecting northern farmers to southern markets and ports. The wealth from groundnut exports also funded schools in Kano, making the city a hub of education and commerce. In Kaduna, textile mills flourished, employing more than 20,000 workers at their peak and supplying fabrics across West Africa. The Bank of the North provided credit to farmers and traders, fueling commerce and production, while the New Nigeria newspaper gave the region a powerful voice in shaping policy and accountability.

But the decline was swift. By the 1970s, Nigeria’s discovery of oil shifted national priorities. Agriculture was neglected, marketing boards weakened, and corruption spread. Farmers abandoned their fields, and the pyramids disappeared. The collapse of the textile industry compounded the decline, while the weakening of financial and media institutions left the North vulnerable.

Today, the North faces insecurity, poverty, and institutional decay. Banditry and terrorism have crippled rural economies, millions of children remain out of school, and health systems are collapsing. Over sixty-five percent of Nigeria’s multidimensionally poor live in the North, with youth unemployment fueling unrest. The recent decision of the Northern States Governors’ Forum to pool two hundred and twenty-eight billion naira annually into a Regional Security Trust Fund is historic. It is a rare moment of unity in a region long plagued by fragmentation. But shields alone cannot rebuild the North. Security must be paired with production, investment, and institution‑building.

The lesson of the pyramids is clear: prosperity comes from organized production, collective investment, and transparent institutions. Reviving the textile industry is paramount. Kaduna and Kano once housed thriving mills that clothed West Africa. Their resurrection through modern machinery, reliable energy, and integration with cotton farming would restore a proud legacy and anchor new opportunities for youth employment and exports. Re-establishing the Bank of the North would provide affordable credit to farmers and SMEs, fueling agro-industrial parks that process groundnut, cotton, rice, and livestock into finished goods. Resurrecting the New Nigeria newspaper would strengthen civic oversight and regional identity.

Instead of sacks of groundnuts, today’s pyramids must be industrial parks, textile factories, financial institutions, media platforms, and education systems. These are the new monuments of progress, built not of produce but of resilience, innovation, and opportunity. They would stand as proof that the North has chosen to rise again.

The coming together of Northern governors is more than a defensive response to insecurity. It is a chance to rebuild the North’s economic backbone, resurrect its lost institutions, and create a new era of prosperity. If seized, the North can once again stand tall—not with pyramids of groundnuts, but with pyramids of progress: industries, jobs, and opportunities rising across the region.

Security will protect the North. Investment will transform it. Together, they can ensure that the region is not just defended, but developed.

For comments, reflection, and further conversation:

📧 Email: samuelagogo4one@yahoo.com

📞 Phone: +2348055847364